Pre-specifying breakpoints and dealing with zero-inflated variables

18 August 2023

Source:vignettes/Pre-specify_brkpts_and_zero-inflated_data.Rmd

Pre-specify_brkpts_and_zero-inflated_data.RmdIntroduction

There may be instances where the dataset of interest has structure that should be accounted for by the model.

For example, devices such as Argos satellite tags on air-breathing marine megafauna may have a variable denoting that the animal has “hauled-out”, meaning that they’re on land. This is particularly common for different seal species, as well as nesting sea turtles. In a similar vein, terrestrial some terrestrial species may go into underground burrows each day to rest, which may be denoted by the loss of a GPS signal until the animal re-emerges. Researchers may also just be interested in the diel patterns of movement exhibited by many species.

Pre-specification of breakpoints

Each of these examples demonstrates a priori knowledge about the species of interest or the inclusion of a variable denoting a specific behavior can be associated with a particular behavior. This knowledge can be directly leveraged by the model that segments the tracks and then clusters them into behavioral states by allowing users to pre-specify breakpoints. These pre-specified breakpoints are then supplied when running the segmentation model and the reversible-jump Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm considers whether to keep them, shift them over, or delete them altogether. In some cases, this can dramatically speed up time to convergence for the Bayesian model. It is worth noting that the model may remove nearly all of the pre-specified breakpoints. In these instances, a number of things may be going wrong: 1) there are too many missing values (NAs) in the data streams, 2) the bins do not characterize the data streams well, and 3) the method or variable used to define the pre-specified breakpoints does not identify any underlying structure in the data streams being analyzed.

Handling of zero-inflated data streams

Another characteristic of some data streams included for analysis are zero-inflated data streams. This means that certain variables have a high number of zeroes with respect to other real numbers or integers. The segmentation-clustering model as well as the clustering-only model that estimates behavioral states at the observation-level can easily account for this structure in the data by lumping all zeroes of a given variable into a single bin of the discretized data stream. This also makes interpretation of the state-dependent distributions quite easy when interpreting each of the different estimated behavioral states.

Handling of missing values

While unrelated to the above topics, it is also worth mentioning that both state estimation models (segment-level or observation-level behavioral states) can handle NAs. This requires no. While there are no specific guidelines on the proportion of NA values that can be included for one or more data streams, those with greater numbers of NAs will hold less weight in influencing the estimation of breakpoints compared to those will full data streams.

A demonstration will be provided below on analyzing a dataset with a

“known” set of possible breakpoints as well as the analysis of a

zero-inflated variable using the built in tracks dataset in

the bayesmove package.

Prepare data

This tutorial works under the assumption that readers have covered the previous vignettes for the segmentation-level state estimation model since there won’t be much description on many of the steps repeated here. First, let’s load in the data and visualize some of its attributes.

library(bayesmove)

library(tidyverse)

library(future)

data(tracks)

# Check data structure

head(tracks)

#> id date x y

#> 1 id1 2020-07-02 11:59:41 0.00000 0.0000000

#> 2 id1 2020-07-02 12:58:26 10.56492 -1.6654990

#> 3 id1 2020-07-02 13:59:31 25.50174 -0.6096675

#> 4 id1 2020-07-02 15:01:27 31.22014 9.5438464

#> 5 id1 2020-07-02 15:59:56 36.15821 19.8737009

#> 6 id1 2020-07-02 16:58:38 39.06810 26.4996352

unique(tracks$id)

#> [1] "id1" "id2" "id3"

Now, let’s calculate step length, turning angle, net-squared displacement, and time step:

tracks<- prep_data(dat = tracks, coord.names = c("x","y"), id = "id")

head(tracks)

#> id date x y step angle NSD dt

#> 1 id1 2020-07-02 11:59:41 0.00000 0.0000000 10.695 NA 0.000 3526

#> 2 id1 2020-07-02 12:58:26 10.56492 -1.6654990 14.974 0.227 114.392 3664

#> 3 id1 2020-07-02 13:59:31 25.50174 -0.6096675 11.653 0.987 650.710 3716

#> 4 id1 2020-07-02 15:01:27 31.22014 9.5438464 11.449 0.067 1065.782 3509

#> 5 id1 2020-07-02 15:59:56 36.15821 19.8737009 7.237 0.032 1702.380 3522

#> 6 id1 2020-07-02 16:58:38 39.06810 26.4996352 0.119 -2.804 2228.547 3738Next, we will round time steps (and dates) to a specified interval (1 h; 3600 s) if within 3 minutes (180 s) of this interval.

tracks<- round_track_time(dat = tracks, id = "id", int = 3600, tol = 180, time.zone = "UTC",

units = "secs")

head(tracks)

#> id date x y step angle NSD dt

#> 1 id1 2020-07-02 11:59:41 0.00000 0.0000000 10.695 NA 0.000 3600

#> 2 id1 2020-07-02 12:59:41 10.56492 -1.6654990 14.974 0.227 114.392 3600

#> 3 id1 2020-07-02 13:59:41 25.50174 -0.6096675 11.653 0.987 650.710 3600

#> 4 id1 2020-07-02 14:59:41 31.22014 9.5438464 11.449 0.067 1065.782 3600

#> 5 id1 2020-07-02 15:59:41 36.15821 19.8737009 7.237 0.032 1702.380 3600

#> 6 id1 2020-07-02 16:59:41 39.06810 26.4996352 0.119 -2.804 2228.547 3600Artificially define ‘resting’ behavior

To demonstrate how to pre-specify breakpoints, I will be creating a synthetic variable that denotes a ‘resting’ behavioral state based on the step length variable. A step like this one in the creation of a derived variable may or may not be necessary for your particular dataset. In this case, I will find the lower quartile of step lengths and use this as the threshold to define the ‘resting’ behavior.

quantile(tracks$step, 0.25, na.rm = T)

#> 25%

#> 0.106Across all three tracks, the lower quartile is almost exactly 0.1, so

this will be the value used as the threshold for a resting vs not

resting state. Additionally, I will change all step length values below

this threshold to zero in order to artificially increase the zeroes in

this datastream. The following code demonstrates how I do this and

create the new binary variable denoting resting from non-resting

observations. Since each of the state estimation models requires the

analysis of discretized variables denoted by positive integers, I will

create a binary rest variable that is denoted by 1 (“rest”)

and 2 (“non-rest”) rather than 0 and 1.

tracks <- tracks %>%

mutate(step = case_when(step <= 0.1 ~ 0,

step > 0.1 ~ step)

) %>%

mutate(rest = case_when(step > 0.1 ~ 2,

step == 0 ~ 1)

)Next, the data need to be reformatted as a list where each element is

a different individual track. As a list object, the data

will then be filtered to only retain observations at a 1 hr (3600 s)

time interval.

# Create list from data frame

tracks.list<- df_to_list(dat = tracks, ind = "id")

# Filter observations

tracks_filt.list<- filter_time(dat.list = tracks.list, int = 3600)Discretize data streams

Before the data streams can be analyzed by the model, they must first be discretized into bins. Further details are provided in the Prepare data for analysis and Cluster observations vignettes. Since the ‘rest’ variable is binary and has already been coded as a 1 or 2, it is already technically discretized. So the remainder of the work needs to be done on the other two data streams included in this analysis, the step lengths and turning angles.

# Define bin number and limits for turning angles

angle.bin.lims=seq(from=-pi, to=pi, by=pi/4) #8 bins

# Define bin number and limits for step lengths

dist.bin.lims=quantile(tracks[tracks$dt == 3600,]$step,

c(0,0.25,0.50,0.75,0.90,1), na.rm=T) #5 bins

angle.bin.lims

#> [1] -3.1415927 -2.3561945 -1.5707963 -0.7853982 0.0000000 0.7853982 1.5707963

#> [8] 2.3561945 3.1415927

dist.bin.lims

#> 0% 25% 50% 75% 90% 100%

#> 0.00000 0.10700 1.27900 5.73825 10.75250 25.25200

# Assign bins to observations

tracks_disc.list<- map(tracks_filt.list,

discrete_move_var,

lims = list(dist.bin.lims, angle.bin.lims),

varIn = c("step", "angle"),

varOut = c("SL", "TA"))Now that we have two new columns in the dataset representing the discretized step lengths (SL) and turning angles (TA), we need to create a 6th bin for step lengths to hold all of the zeroes. This is because they are currently all stored within the first bin with other non-zero values.

# Since 0s get lumped into bin 1 for SL, need to add a 6th bin to store only 0s

tracks_disc.list2 <- tracks_disc.list %>%

map(., ~mutate(.x, SL = SL + 1)) %>% #to shift bins over from 1-5 to 2-6

map(., ~mutate(.x, SL = case_when(step == 0 ~ 1, #assign 0s to bin 1

step != 0 ~ SL) #otherwise keep the modified SL bin

))Segment the tracks

With the newly discretized data streams, the tracks can now be analyzed by the segmentation model. However, we still have yet to pre-sepcify the breakpoints.

Pre-specify breakpoints

To pre-specify breakpoints, users will apply the

find_breaks() function. In its standard form, this function

can only be applied to one track at a time, so we will use

purrr::map() to map this function across each of the list

elements (i.e. different tracks). We also need to supply a character

vector to the argument ind, which indicates the column name

on which we would like to identify possible breakpoints. This function

only works on discrete variables (i.e., integers), so users will need to

potentially modify the variable supplied or modify this function to meet

the needs of their data. If pre-specifying breakpoints for dates to

denote diel patterns, users could potentially apply this function to the

day-of-year or Julian day.

Since the pre-specified breakpoints must be supplied to the model as

a list, the resulting breaks object shows how

these potential breakpoints should be stored.

# Only retain id, discretized step length (SL), turning angle (TA), and rest columns

tracks.list2<- map(tracks_disc.list2,

subset,

select = c(id, SL, TA, rest))

# Pre-specify breakpoints based on 'rest'

breaks<- map(tracks.list2, ~find_breaks(dat = ., ind = "rest"))Run the segmentation model

set.seed(1)

# Define hyperparameter for prior distribution

alpha<- 1

# Set number of iterations for the Gibbs sampler

ngibbs<- 50000

# Set the number of bins used to discretize each data stream

nbins<- c(6,8,2) #SL, TA, rest (in the order from left to right in tracks.list2)

progressr::handlers(progressr::handler_progress(clear = FALSE))

future::plan(future::multisession, workers = 3) #run all MCMC chains in parallel

#refer to future::plan() for more details

dat.res<- segment_behavior(data = tracks.list2, ngibbs = ngibbs, nbins = nbins,

alpha = alpha, breakpt = breaks)

#> 52.259 sec elapsed

# takes 1.5 min to run

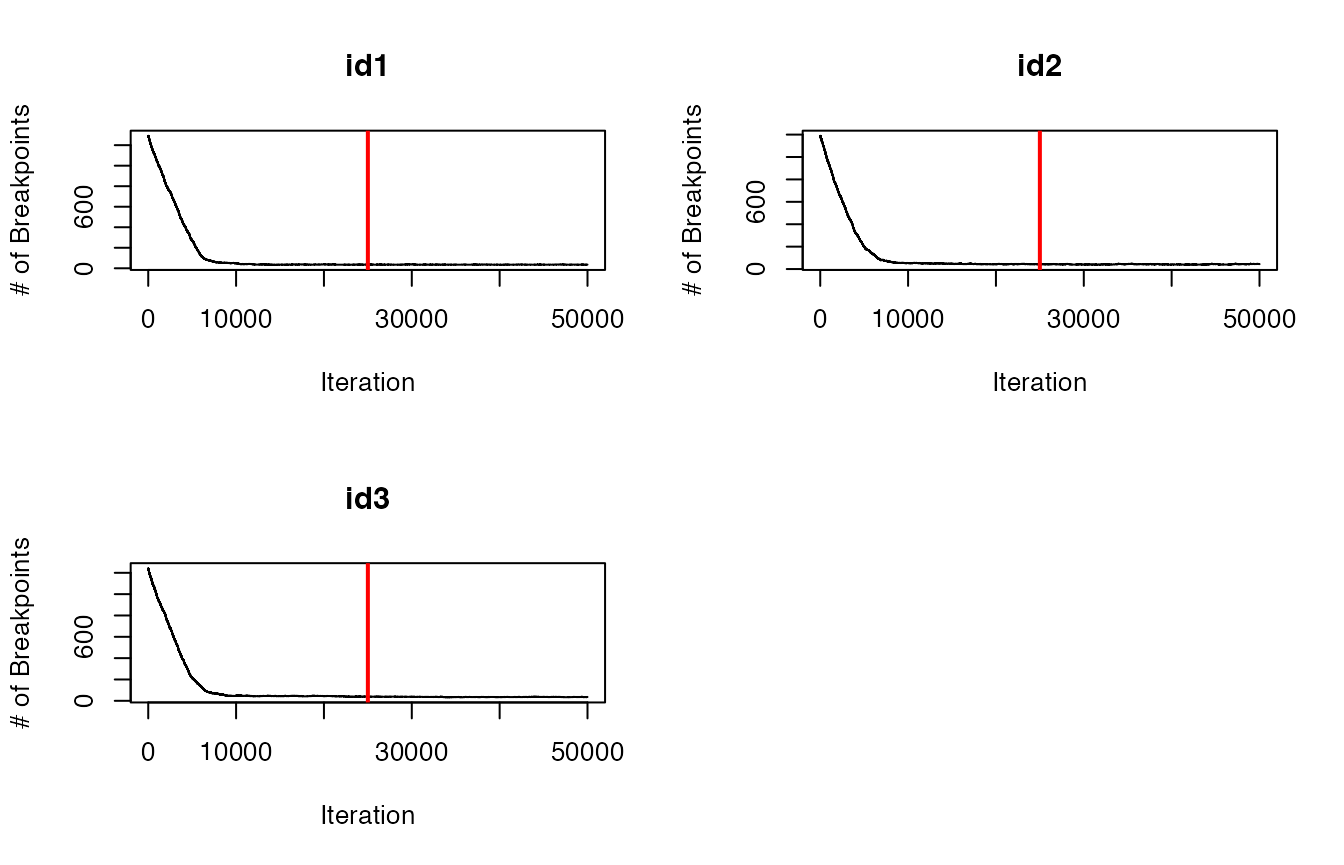

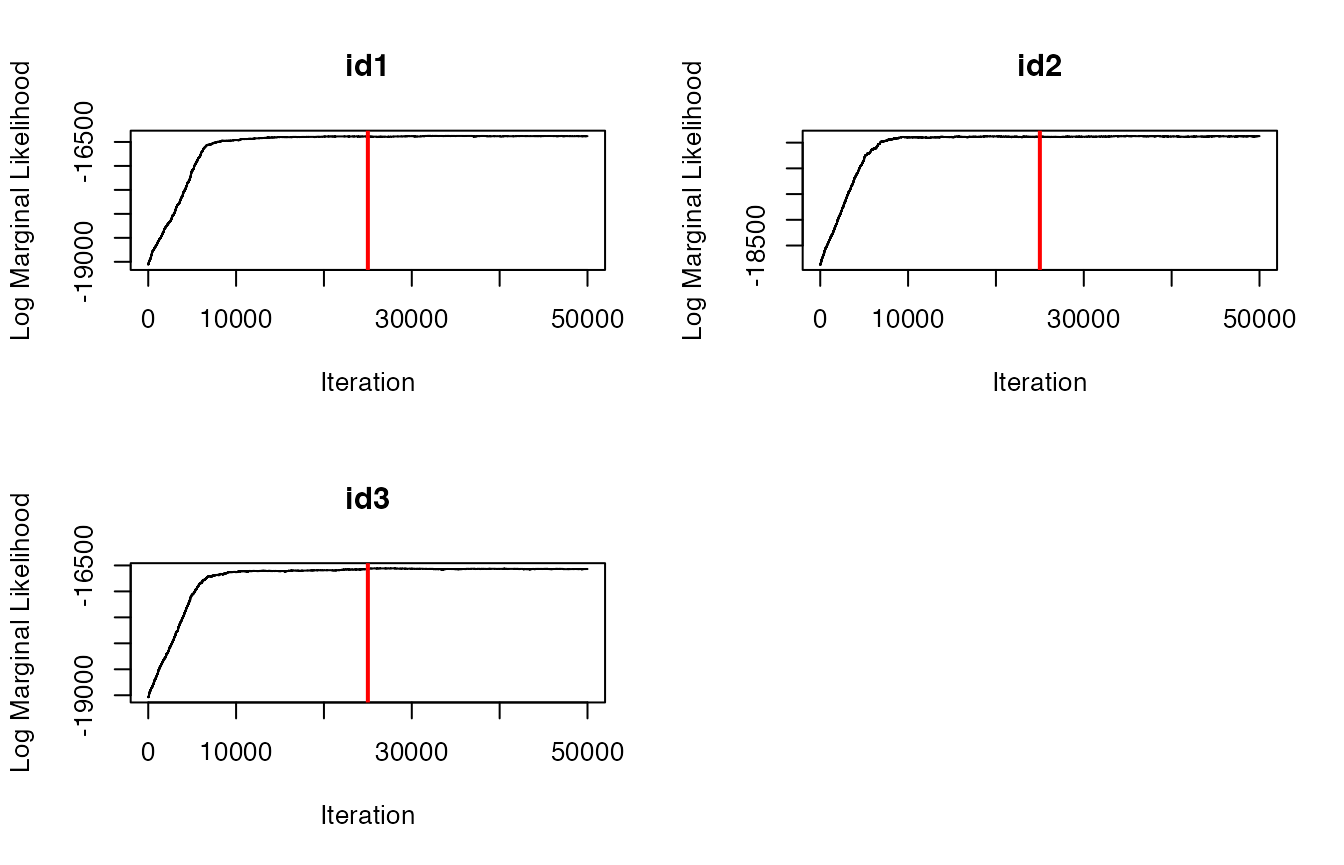

future::plan(future::sequential) #return to single coreBefore we proceed further with these estimated breakpoints from the model, let’s check that it has converged first by inspecting traceplots of the log marginal likelihood and the number of breakpoints.

# Trace-plots for the number of breakpoints per ID

traceplot(data = dat.res, type = "nbrks")

# Trace-plots for the log marginal likelihood (LML) per ID

traceplot(data = dat.res, type = "LML")

#both plots appear to indicate convergence to posteriorEverything looks good from the traceplots, so now let’s identify the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate that we’ll use in the next step.

## Determine MAP for selecting breakpoints

MAP.est<- get_MAP(dat = dat.res$LML, nburn = 25000)

MAP.est

#> [1] 32049 34861 26213

brkpts<- get_breakpts(dat = dat.res$brkpts, MAP.est = MAP.est)

# How many breakpoints estimated per ID?

apply(brkpts[,-1], 1, function(x) length(purrr::discard(x, is.na)))

#> id1 id2 id3

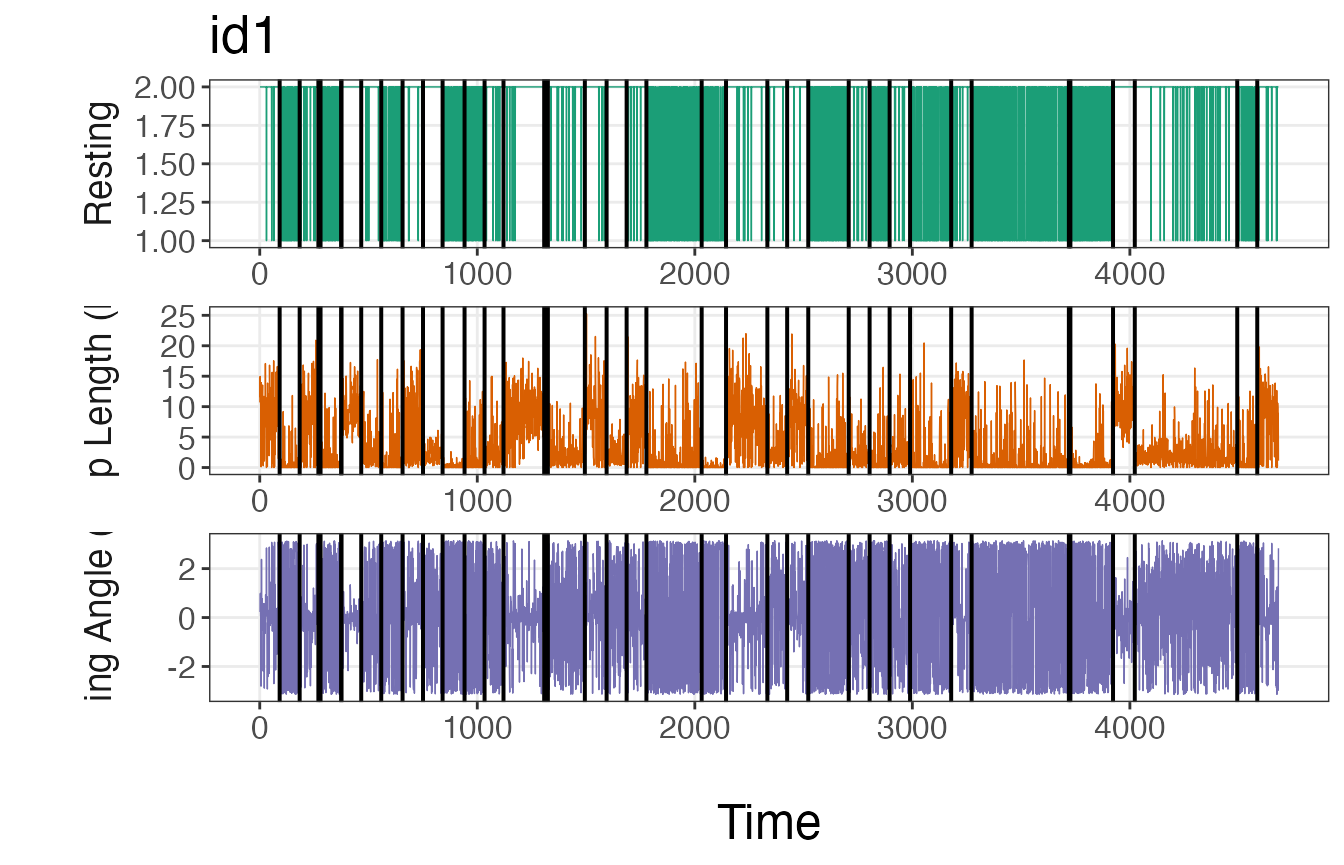

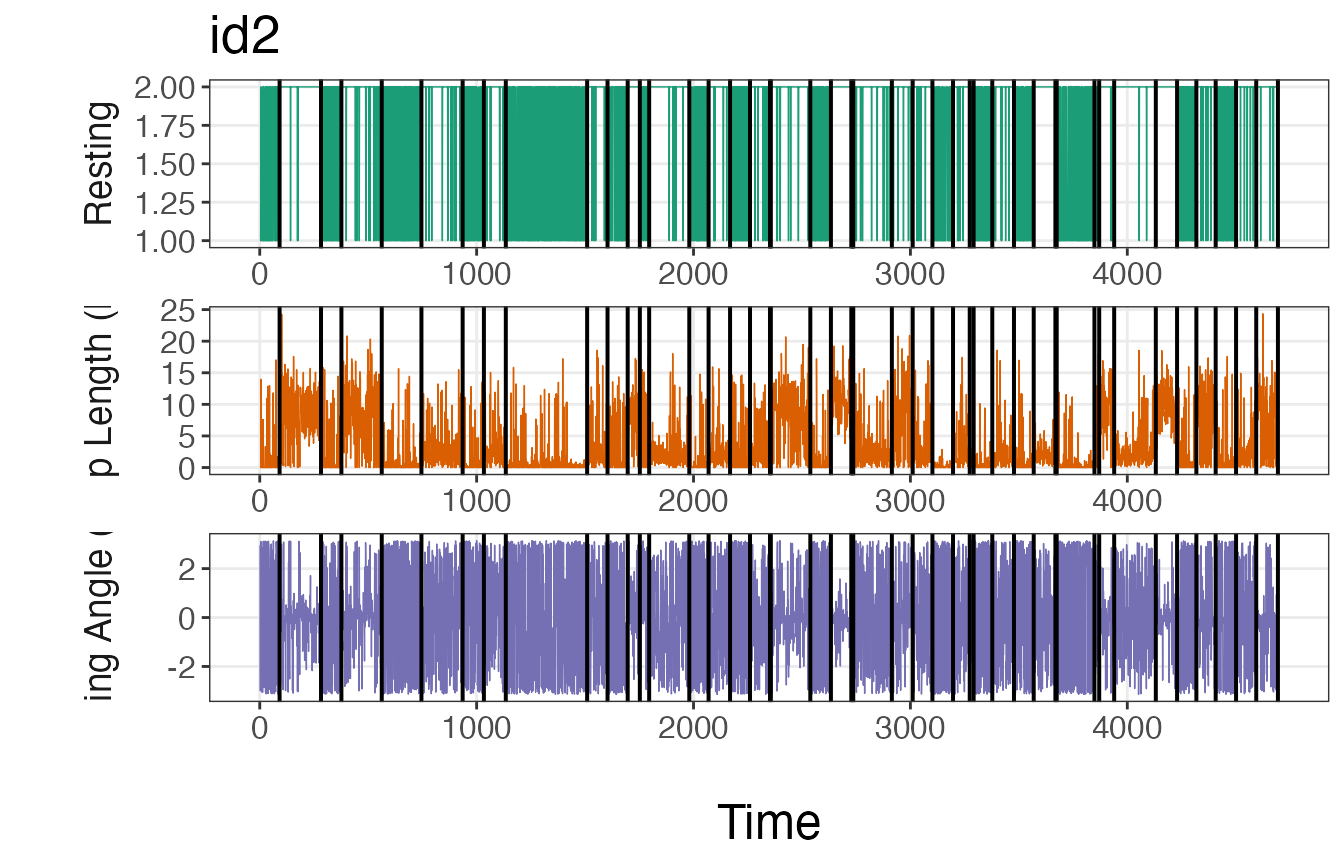

#> 37 45 40Another good visual diagnostic to check how well the model is able to identify major breakpoints consistent with a user’s a priori knowledge is to plot the breakpoints over the analyzed data streams.

plot_breakpoints(data = tracks_disc.list2, as_date = FALSE, var_names = c("step","angle","rest"),

var_labels = c("Step Length (km)", "Turning Angle (rad)", "Resting"), brkpts = brkpts)

If these plots match up with intuition, then it is safe to move forward with the estimated breakpoints. If the number or location of these breakpoints deviate from expectations, it may be necessary to run the model again with a greater number of iterations or using a different method to discretize the data streams.

Assign track segments to tracks

With the modeled breakpoints, users will need to assign track segment

numbers to each individual. This is performed using the

assign_tseg() function.

tracks.seg<- assign_tseg(dat = tracks_disc.list2, brkpts = brkpts)

head(tracks.seg)

#> id date x y step angle NSD dt rest

#> 1 id1 2020-07-02 11:59:41 0.00000 0.0000000 10.695 NA 0.000 3600 2

#> 2 id1 2020-07-02 12:59:41 10.56492 -1.6654990 14.974 0.227 114.392 3600 2

#> 3 id1 2020-07-02 13:59:41 25.50174 -0.6096675 11.653 0.987 650.710 3600 2

#> 4 id1 2020-07-02 14:59:41 31.22014 9.5438464 11.449 0.067 1065.782 3600 2

#> 5 id1 2020-07-02 15:59:41 36.15821 19.8737009 7.237 0.032 1702.380 3600 2

#> 6 id1 2020-07-02 16:59:41 39.06810 26.4996352 0.119 -2.804 2228.547 3600 2

#> obs time1 SL TA tseg

#> 1 1 1 5 NA 1

#> 2 2 2 6 5 1

#> 3 3 3 6 6 1

#> 4 4 4 6 5 1

#> 5 5 5 5 5 1

#> 6 6 6 3 1 1Cluster the segments

With track segments now denoted from the segmentation model, the next

step is to cluster these segments together into behavioral states using

Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) using the

cluster_segments() function. But first, we need to count

the number of observations per segment that belong in each of the

discretized bins.

# Select only id, tseg, SL, TA, and rest columns

tracks.seg2<- tracks.seg[,c("id","tseg","SL","TA","rest")]

# Summarize observations by track segment

nbins<- c(6,8,2)

obs<- summarize_tsegs(dat = tracks.seg2, nbins = nbins)

head(obs)

#> id tseg y1.1 y1.2 y1.3 y1.4 y1.5 y1.6 y2.1 y2.2 y2.3 y2.4 y2.5 y2.6 y2.7

#> 1 id1 1 4 0 7 13 44 24 7 4 1 26 38 7 0

#> 2 id1 2 53 0 24 8 6 1 40 7 3 3 3 5 5

#> 3 id1 3 9 0 6 10 34 27 5 5 4 39 22 4 1

#> 4 id1 4 0 0 2 4 3 1 1 0 1 1 2 3 0

#> 5 id1 5 50 0 28 8 6 3 33 9 2 6 4 2 8

#> 6 id1 6 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0

#> y2.8 y3.1 y3.2

#> 1 8 4 88

#> 2 26 53 39

#> 3 6 9 77

#> 4 2 0 10

#> 5 31 50 45

#> 6 0 0 1Run the clustering model

set.seed(1)

# Prepare for Gibbs sampler

ngibbs<- 1000 #number of MCMC iterations for Gibbs sampler

nburn<- ngibbs/2 #number of iterations for burn-in

nmaxclust<- max(nbins) - 1 #one fewer than max number of bins used for data streams

ndata.types<- length(nbins) #number of data types

# Priors

gamma1<- 0.1

alpha<- 0.1

# Run LDA model

res<- cluster_segments(dat=obs, gamma1=gamma1, alpha=alpha,

ngibbs=ngibbs, nmaxclust=nmaxclust,

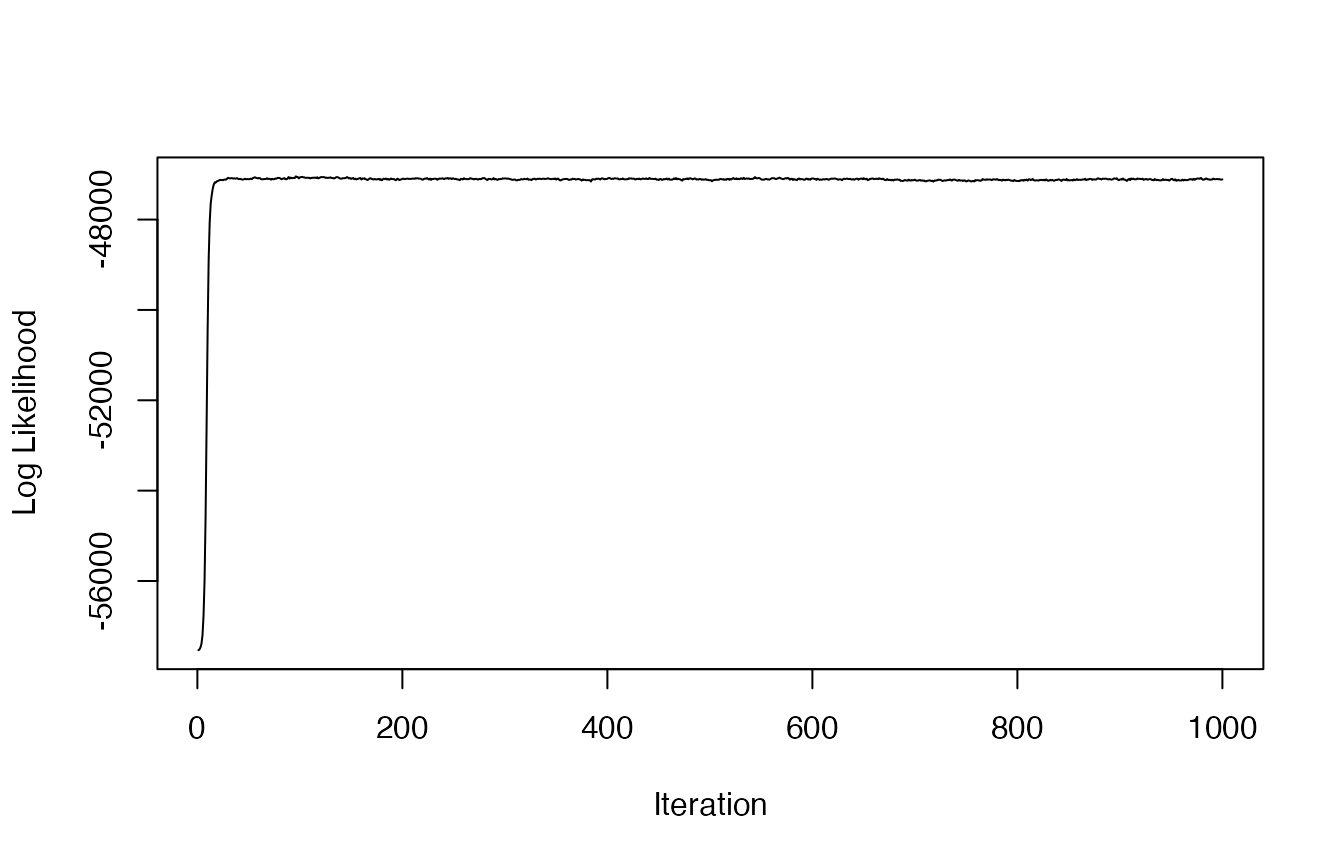

nburn=nburn, ndata.types=ndata.types)Again, let’s check the traceplot of the log likelihood to check if the LDA clustering model converged on the posterior distribution.

plot(res$loglikel, type='l', xlab = "Iteration", ylab = "Log Likelihood")

#LDA appears to have convergedDetermine the number of likely states

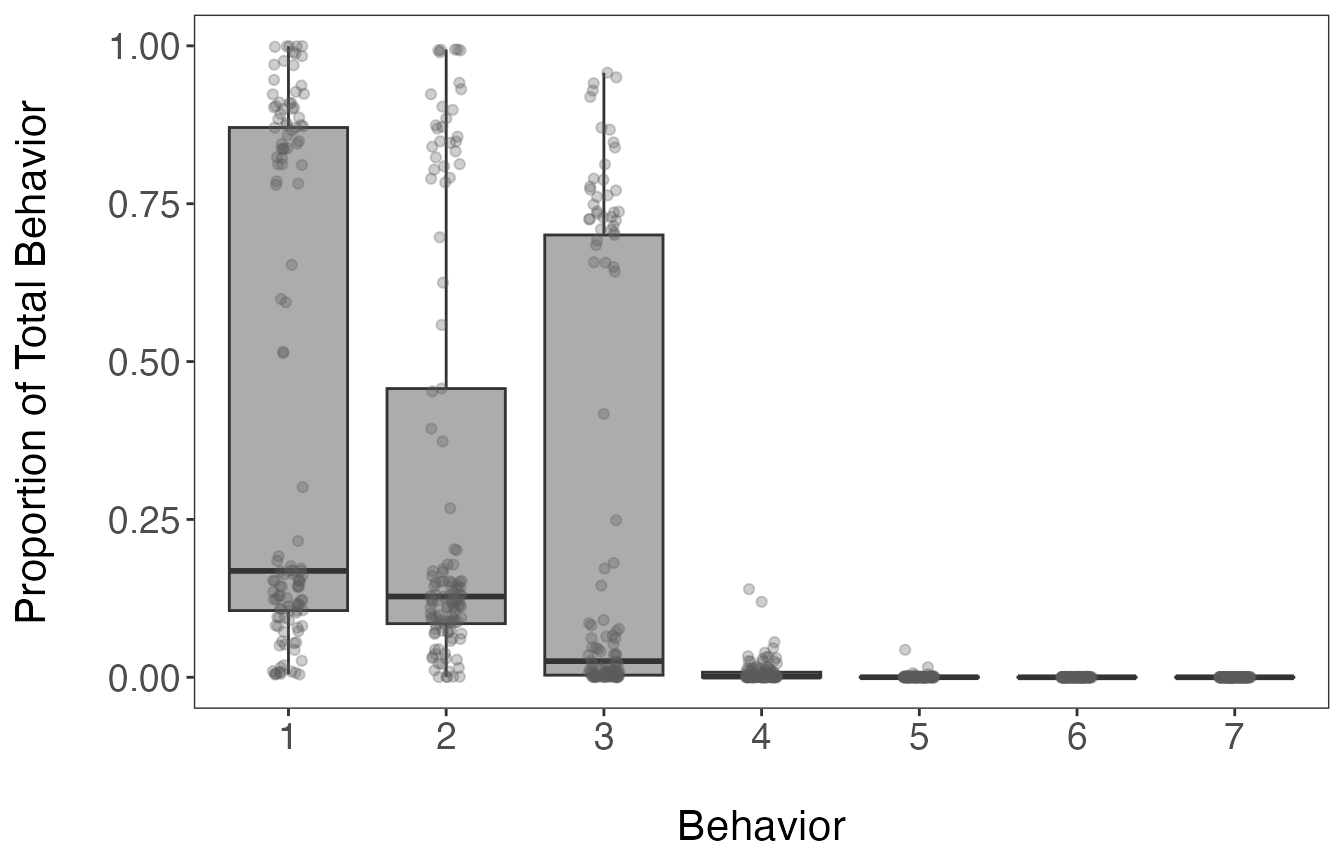

To determine the number of likely states estimated by the model, we’ll need to inspect the results from the \(\theta\) parameter. This is a matrix that stores the probability of a segment belonging to a particular behavioral state. We will try to select the fewest number of states that account for \(\ge 90\%\) of all observations.

# Extract proportions of behaviors per track segment

theta.estim<- extract_prop(res = res, ngibbs = ngibbs, nburn = nburn, nmaxclust = nmaxclust)

# Calculate mean proportions per behavior

(theta.means<- round(colMeans(theta.estim), digits = 3))

#> [1] 0.439 0.298 0.254 0.008 0.001 0.000 0.000

# Calculate cumulative sum

cumsum(theta.means)

#> [1] 0.439 0.737 0.991 0.999 1.000 1.000 1.000

#first 3 states comprise 99.1% of all observations

# Convert to data frame for ggplot2

theta.estim_df<- theta.estim %>%

as.data.frame() %>%

pivot_longer(., cols = 1:all_of(nmaxclust), names_to = "behavior", values_to = "prop") %>%

modify_at("behavior", factor)

levels(theta.estim_df$behavior)<- 1:nmaxclust

# Plot results

ggplot(theta.estim_df, aes(behavior, prop)) +

geom_boxplot(fill = "grey35", alpha = 0.5, outlier.shape = NA) +

geom_jitter(color = "grey35", position = position_jitter(0.1),

alpha = 0.3) +

labs(x="\nBehavior", y="Proportion of Total Behavior\n") +

theme_bw() +

theme(panel.grid = element_blank(),

axis.title = element_text(size = 16),

axis.text = element_text(size = 14))

The inspection of the mean proportions of behavioral states stored in

the theta.estim object shows that the first 3 states are

attributed to 99.1% of observations. All of the estimates per segment

and behavioral state are shown in the above boxplot.

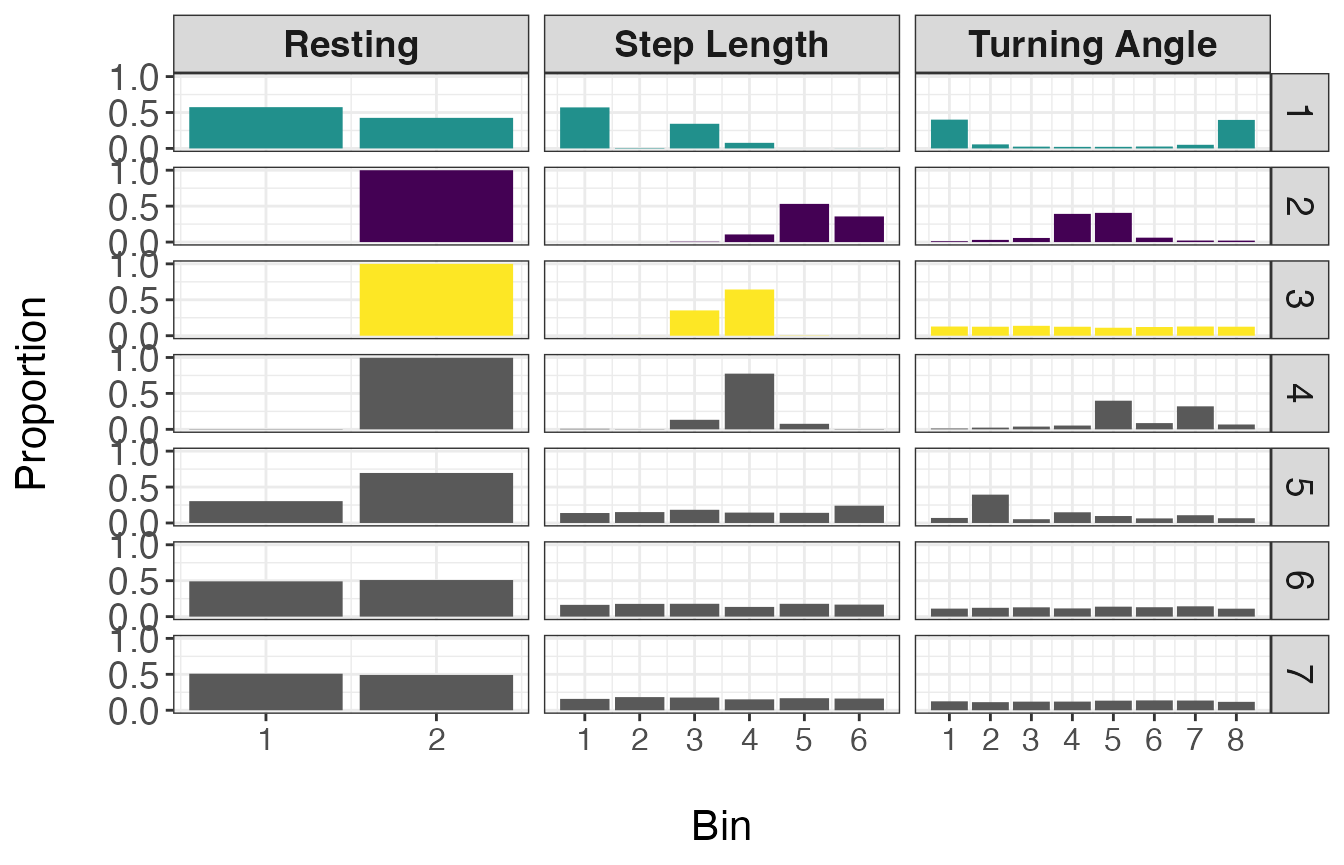

Classify the states as behaviors

Now that it appears that 3 states are likely present in this dataset,

we need to extract the state-dependent distributions from the \(\phi\) matrix using the

get_behav_hist() function. By visualizing these

distributions, we can verify the findings determined using the \(\theta\) matrix and assign names to the

states based on the shape of the state-dependent distributions. Below,

only the retained states have distributions shown in color. The

remaining 4 states are included to demonstrate that they are not

biologically interpretable by comparison.

# Extract bin estimates from phi matrix

behav.res<- get_behav_hist(dat = res, nburn = nburn, ngibbs = ngibbs, nmaxclust = nmaxclust,

var.names = c("Step Length","Turning Angle","Resting"))

# Plot histograms of proportion data

ggplot(behav.res, aes(x = bin, y = prop, fill = as.factor(behav))) +

geom_bar(stat = 'identity') +

labs(x = "\nBin", y = "Proportion\n") +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.title = element_text(size = 16),

axis.text.y = element_text(size = 14),

axis.text.x.bottom = element_text(size = 12),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14),

strip.text.x = element_text(face = "bold")) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("#21908CFF","#440154FF","#FDE725FF",

"grey35","grey35","grey35","grey35"), guide = "none") +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = c(0.00, 0.50, 1.00)) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = 1:8) +

facet_grid(behav ~ var, scales = "free_x")

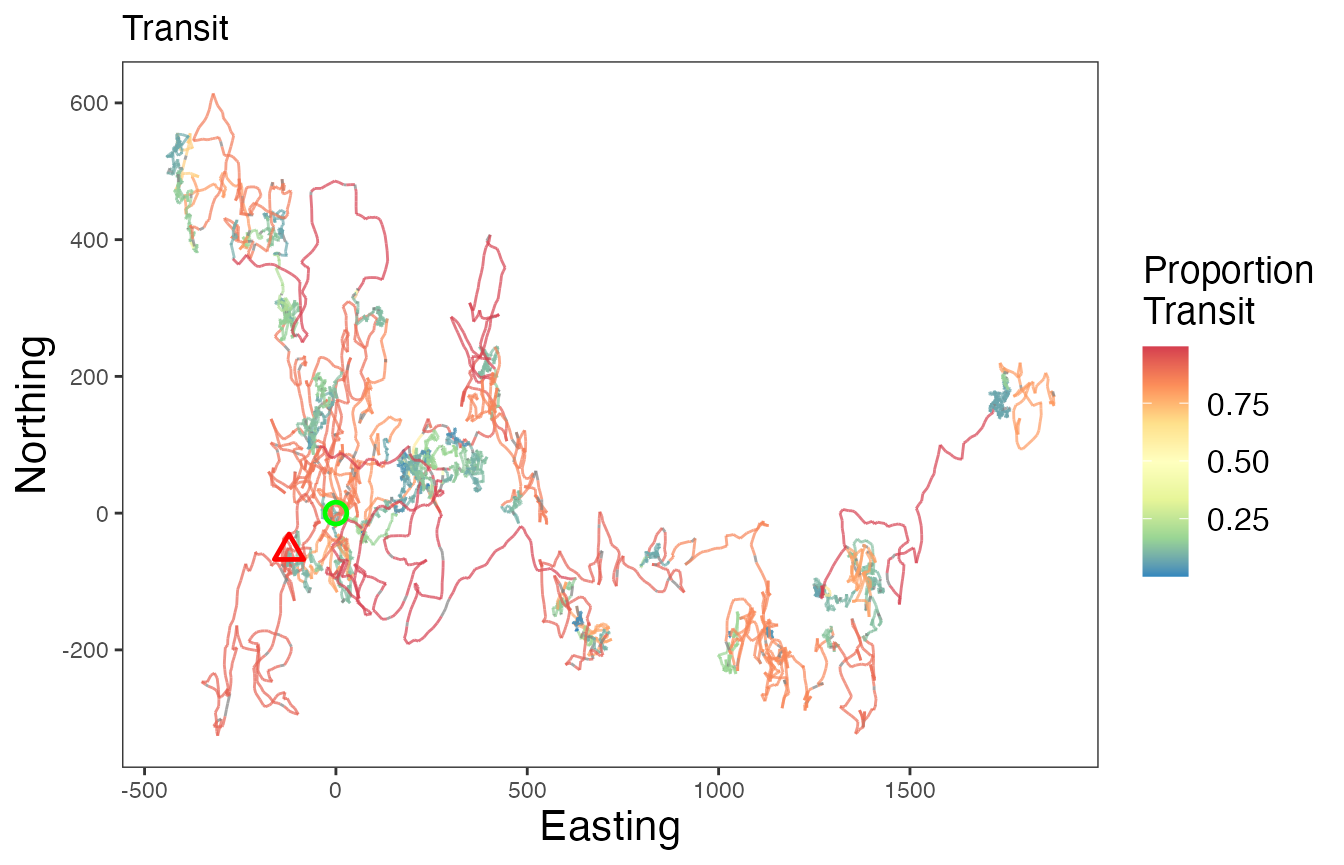

From the above plot, it appears that state 1 has a high number of resting observations (bin 1 of Resting), short step lengths (primarily zero as exemplified by the high proportion in bin 1), and high turning angles (near \(\pi\) or \(-\pi\)). Given these distributions, I will call state 1 ‘Resting’. States 2 and 3 have zero observations with resting behavior, but state 2 has larger step lengths and turning angles closer to zero, indicating relatively straight movements. Therefore state 2 will be called ‘Transit’ and state 3 will be called ‘Exploratory’.

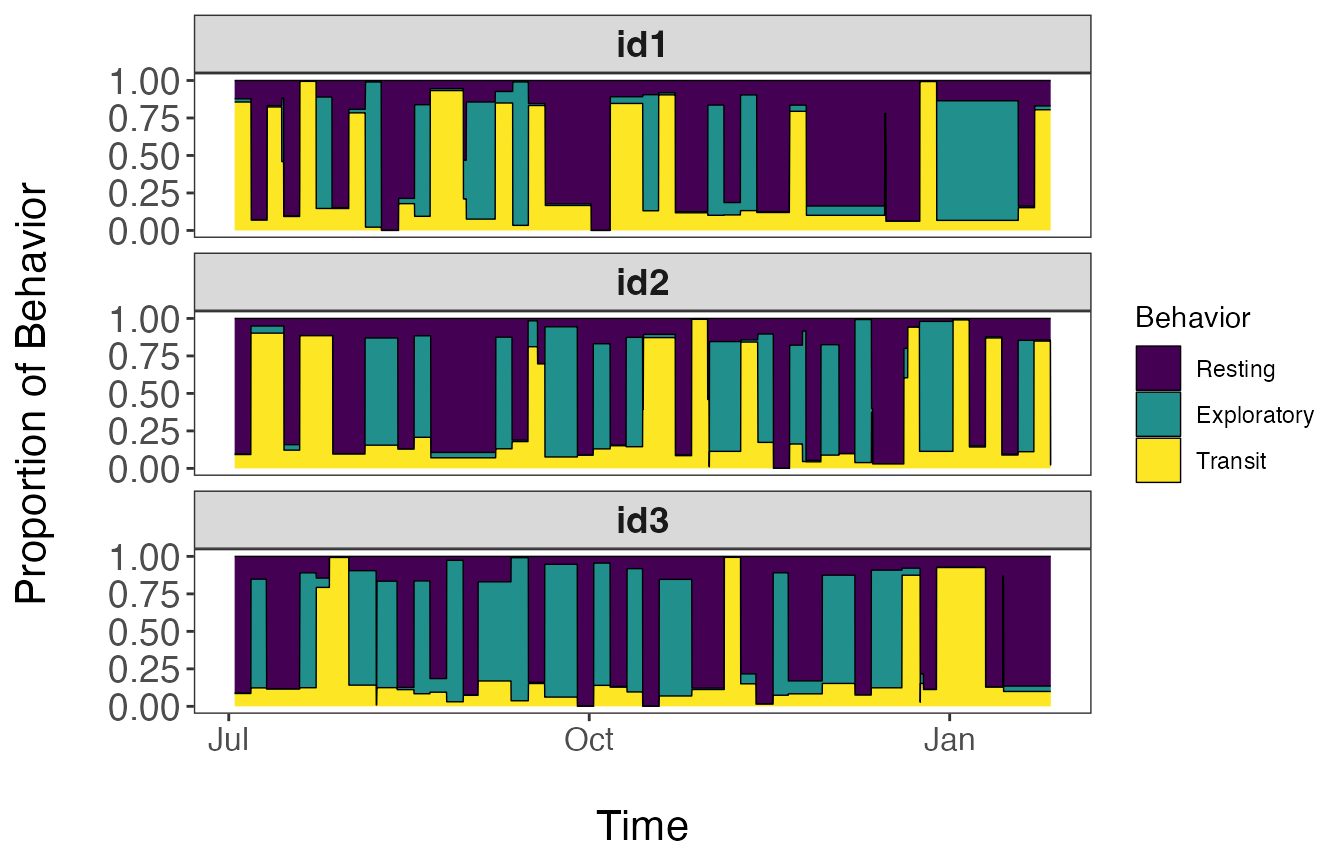

Since each segment is defined as a mixture of the different behavioral states, we will need to assign these proportions back to our dataset. These proportions can also be visualized over time.

# Reformat proportion estimates for all track segments

theta.estim.long<- expand_behavior(dat = tracks.seg, theta.estim = theta.estim, obs = obs,

nbehav = 3, behav.names = c("Resting", "Transit", "Exploratory"),

behav.order = c(1,3,2))

# Plot results

ggplot(theta.estim.long) +

geom_area(aes(x=date, y=prop, fill = behavior), color = "black", linewidth = 0.25,

position = "fill") +

labs(x = "\nTime", y = "Proportion of Behavior\n") +

scale_fill_viridis_d("Behavior") +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.title = element_text(size = 16),

axis.text.y = element_text(size = 14),

axis.text.x.bottom = element_text(size = 12),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14, face = "bold"),

panel.grid = element_blank()) +

facet_wrap(~id, nrow = 3)

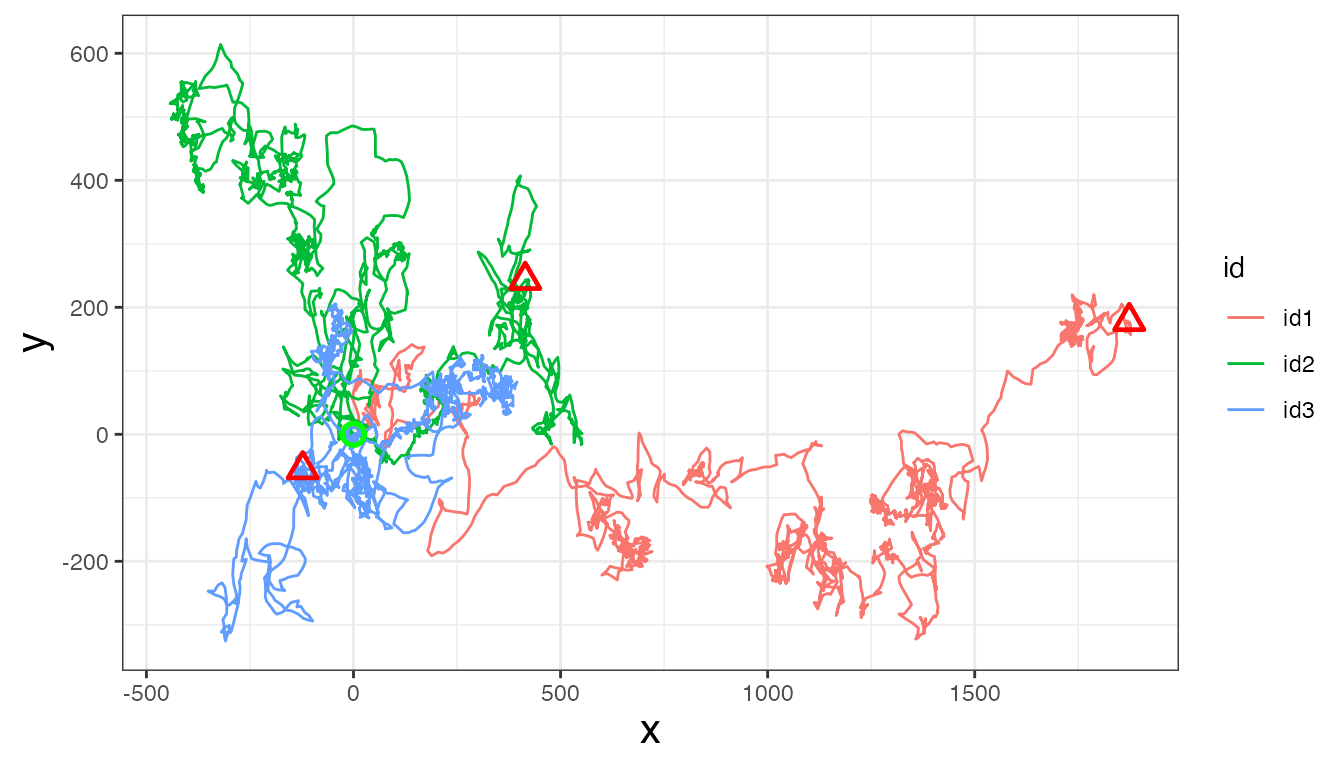

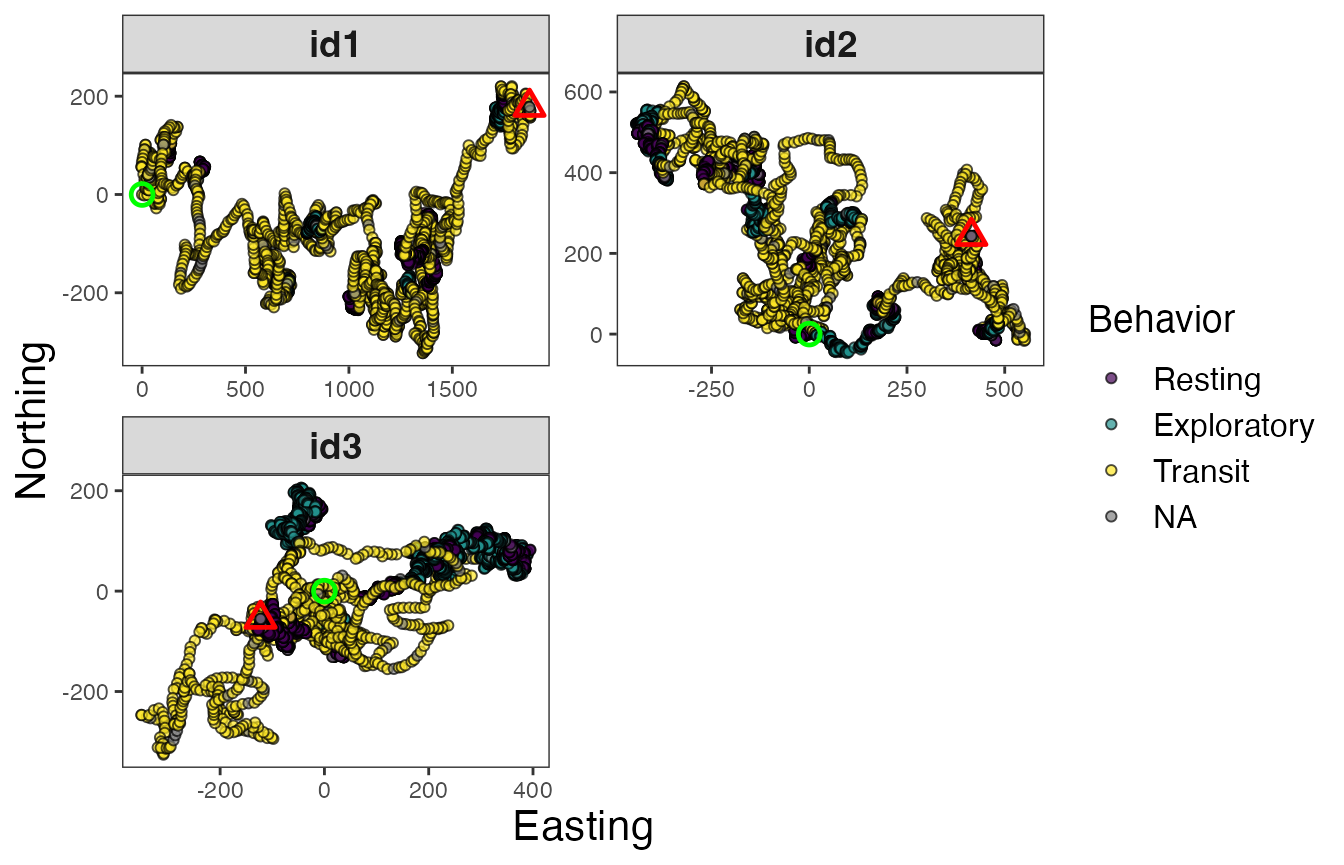

Assign behavioral states to tracks

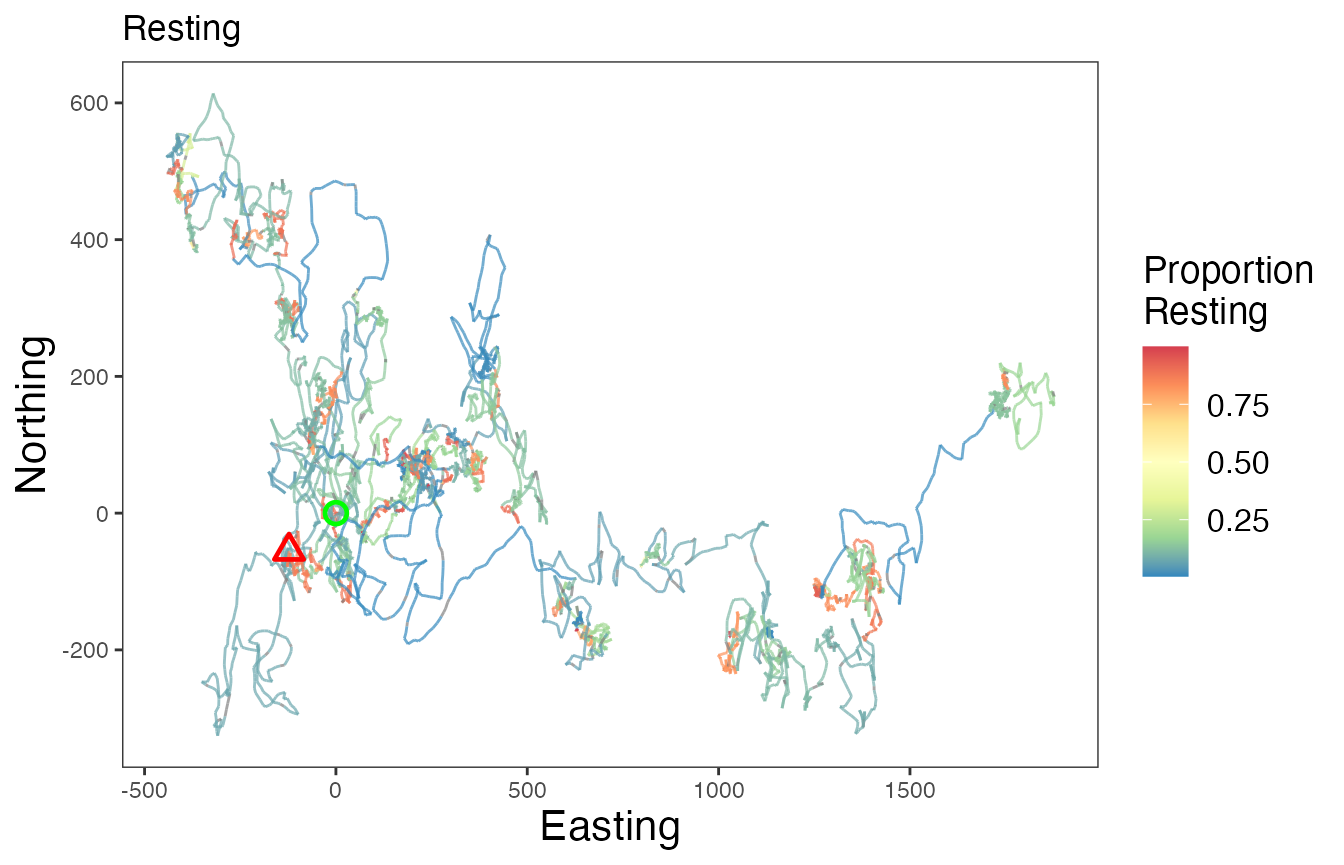

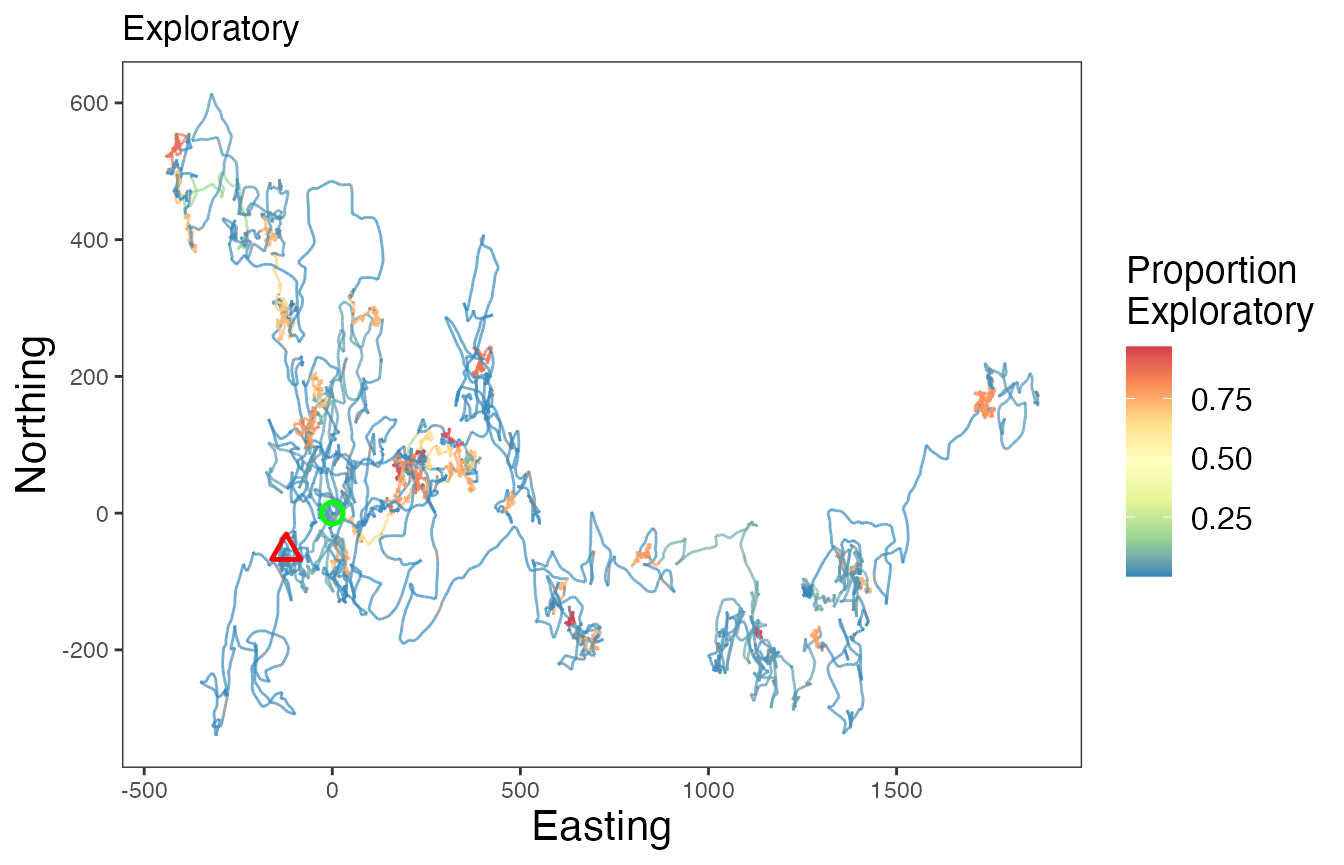

The last major step is to now assign the behavioral states back to the original tracks. More specifically, the proportion of each behavioral state assigned to each track segment will be associated with all observations in that particular track segment. When mapping these results, users can either plot the dominant behavior per observation or potentially the proportion associated with a given behavioral state of interest.

# Merge results with original data

tracks.out<- assign_behavior(dat.orig = tracks,

dat.seg.list = df_to_list(tracks.seg, "id"),

theta.estim.long = theta.estim.long,

behav.names = c("Resting","Exploratory","Transit"))

# Map dominant behavior for all IDs

ggplot() +

geom_path(data = tracks.out, aes(x=x, y=y), color="gray60", linewidth=0.25) +

geom_point(data = tracks.out, aes(x, y, fill=behav), size=1.5, pch=21, alpha=0.7) +

geom_point(data = tracks.out %>%

group_by(id) %>%

slice(which(row_number() == 1)) %>%

ungroup(), aes(x, y), color = "green", pch = 21, size = 3, stroke = 1.25) +

geom_point(data = tracks.out %>%

group_by(id) %>%

slice(which(row_number() == n())) %>%

ungroup(), aes(x, y), color = "red", pch = 24, size = 3, stroke = 1.25) +

scale_fill_viridis_d("Behavior", na.value = "grey50") +

labs(x = "Easting", y = "Northing") +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.title = element_text(size = 16),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14, face = "bold"),

panel.grid = element_blank()) +

guides(fill = guide_legend(label.theme = element_text(size = 12),

title.theme = element_text(size = 14))) +

facet_wrap(~id, scales = "free", ncol = 2)

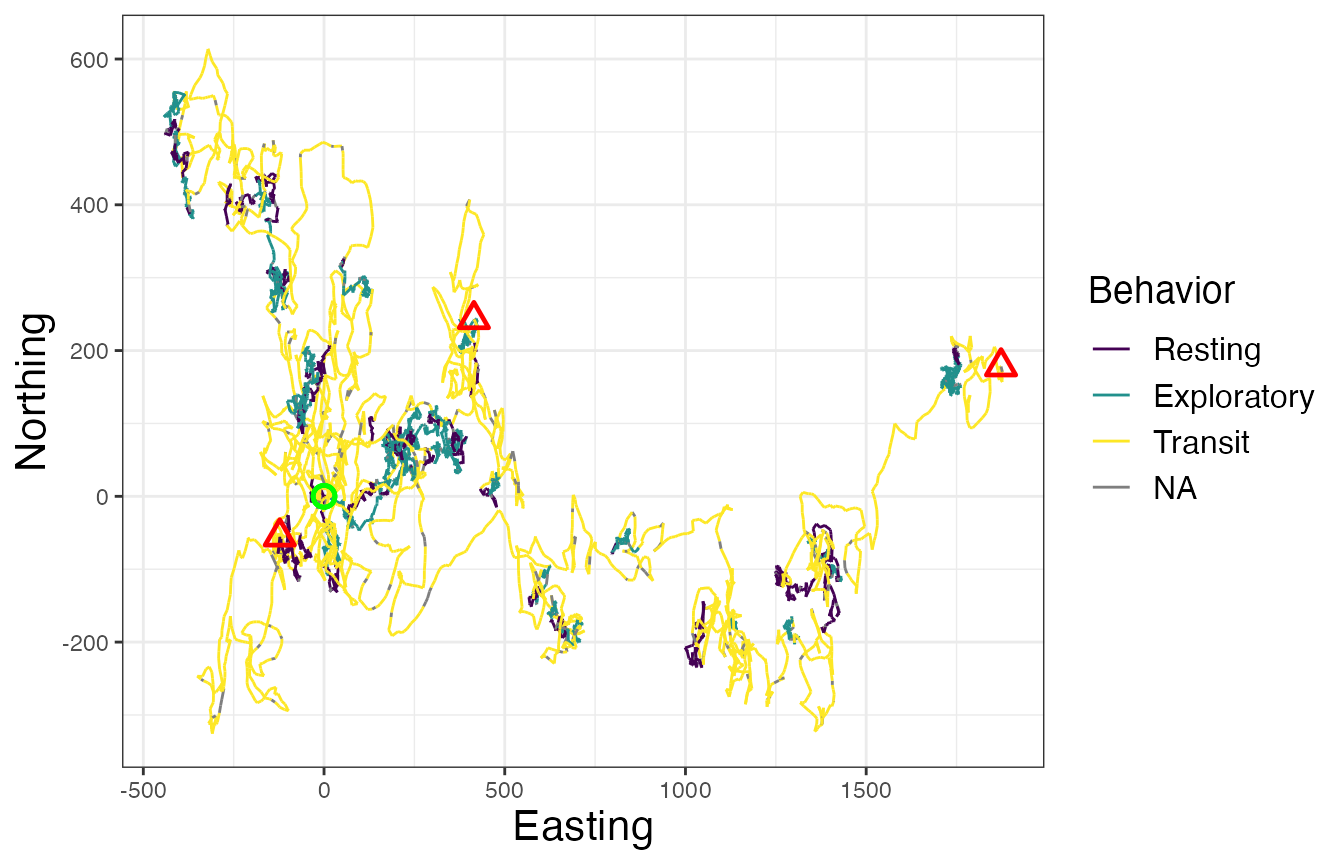

# Map of all IDs

ggplot() +

geom_path(data = tracks.out, aes(x, y, color = behav, group = id), linewidth=0.5) +

geom_point(data = tracks.out %>%

group_by(id) %>%

slice(which(row_number() == 1)) %>%

ungroup(), aes(x, y), color = "green", pch = 21, size = 3, stroke = 1.25) +

geom_point(data = tracks.out %>%

group_by(id) %>%

slice(which(row_number() == n())) %>%

ungroup(), aes(x, y), color = "red", pch = 24, size = 3, stroke = 1.25) +

scale_color_viridis_d("Behavior", na.value = "grey50") +

labs(x = "Easting", y = "Northing") +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.title = element_text(size = 16),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14, face = "bold"),

legend.text = element_text(size = 12),

legend.title = element_text(size = 14))

# Proportion resting

ggplot() +

geom_path(data = tracks.out, aes(x, y, color = Resting, group = id),

linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.7) +

geom_point(data = tracks.out %>%

slice(which(row_number() == 1)),

aes(x, y), color = "green", pch = 21, size = 3, stroke = 1.25) +

geom_point(data = tracks.out %>%

slice(which(row_number() == n())),

aes(x, y), color = "red", pch = 24, size = 3, stroke = 1.25) +

scale_color_distiller("Proportion\nResting", palette = "Spectral", na.value = "grey50") +

labs(x = "Easting", y = "Northing", title = "Resting") +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.title = element_text(size = 16),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14, face = "bold"),

panel.grid = element_blank(),

legend.text = element_text(size = 12),

legend.title = element_text(size = 14))

# Proportion exploratory

ggplot() +

geom_path(data = tracks.out, aes(x, y, color = Exploratory, group = id),

linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.7) +

geom_point(data = tracks.out %>%

slice(which(row_number() == 1)),

aes(x, y), color = "green", pch = 21, size = 3, stroke = 1.25) +

geom_point(data = tracks.out %>%

slice(which(row_number() == n())),

aes(x, y), color = "red", pch = 24, size = 3, stroke = 1.25) +

scale_color_distiller("Proportion\nExploratory", palette = "Spectral", na.value = "grey50") +

labs(x = "Easting", y = "Northing", title = "Exploratory") +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.title = element_text(size = 16),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14, face = "bold"),

panel.grid = element_blank(),

legend.text = element_text(size = 12),

legend.title = element_text(size = 14))

# Proportion transit

ggplot() +

geom_path(data = tracks.out, aes(x, y, color = Transit, group = id),

linewidth=0.5, alpha=0.7) +

geom_point(data = tracks.out %>%

slice(which(row_number() == 1)),

aes(x, y), color = "green", pch = 21, size = 3, stroke = 1.25) +

geom_point(data = tracks.out %>%

slice(which(row_number() == n())),

aes(x, y), color = "red", pch = 24, size = 3, stroke = 1.25) +

scale_color_distiller("Proportion\nTransit", palette = "Spectral", na.value = "grey50") +

labs(x = "Easting", y = "Northing", title = "Transit") +

theme_bw() +

theme(axis.title = element_text(size = 16),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14, face = "bold"),

panel.grid = element_blank(),

legend.text = element_text(size = 12),

legend.title = element_text(size = 14))